[fshow photosetid=72157629857185014]

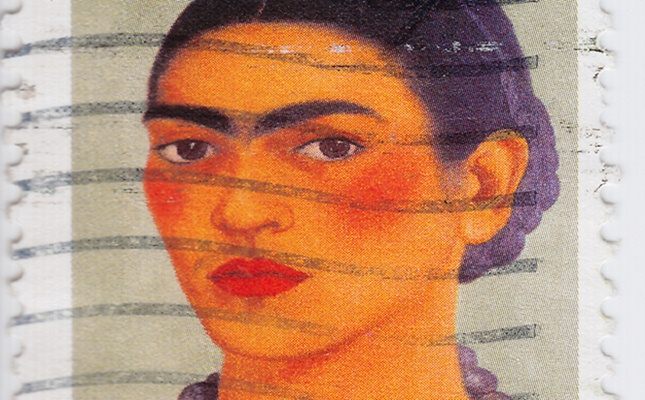

A couple of weeks ago, I watched Frida, the 2002 biographical film about the private and professional life of Kahlo, starring Salma Hayek as Kahlo and Alfred Molina as her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera. The film depicted the artist as a raw yet refined woman and just like the dance, had a lasting impression on me. So when I had the chance to visit Mexico City later the same year, I decided to include La Casa Azul, the childhood home-turned-museum of Kahlo on my ‘must-see’ list.

Pain and passion

During a recent visit to an International Festival of Dance and Music in my home city, I saw the most amazing dance performance. The festival is one of the highlights in the rather sparse cultural calendar and therefore offers a welcome chance to see performances from around the world right on my own doorstep. Over the years, I have seen many excellent performances, but none as impressive as this one. Performed by a Donlon dance company, it was inspired by late Mexican painter Frida Kahlo and displayed all the colour, intensity and often-cited ‘pain and passion’ of Kahlo herself.

The Blue House

Kahlo’s father, Guillermo Kahlo, built La Casa Azul, which means The Blue House, in 1907, the year Kahlo was born. The colonial style house remains in its original u-shape, built around a central courtyard and framed by cobalt blue walls. Kahlo grew up in the house and later shared it with Rivera, who upon his death in 1957 donated it to become a museum the following year. While the couple lived in the house it was a gathering point for many internationally renowned artists and intellectuals including Sergei Einstein, Nelson Rockefeller, George Gershwin and Maria Felix. When Leon Trotsky immigrated from Russia, Kahlo and Rivera, both passionate communists, welcomed him into La Casa Azul, only for Kahlo to begin an affair with Trotsky, which ended Kahlo and Revira’s first marriage.

Two Fridas

Upon entering the house from the courtyard, I first entered the former living room, which has been converted into a gallery featuring some of Kahlo’s original paintings. One painting struck me in particular – perhaps because it invoked in me the same mystery and awe that both the dance performance and the film had – a copy of the ‘The two Fridas’ painted during Kahlo and Rivera’s divorce in 1939. Like many of Kahlo’s other paintings this one is a dual self portrait of Kahlo largely believed to be an expression of her feelings at the time. The picture showed two Kahlos, one wearing traditional Mexican garments, the attire Rivera much preferred his wife to wear, the other wearing European dress. In the painting, the women are connected by a vein-like string at their necks, as well as holding each others hands. The Kahlo in the European dress has a bleeding heart, bloodstains on her dress and is holding a pair of scissors in her hands symbolising her broken marriage, while the Kahlo in the traditional Mexican dress still has an unblemished heart and holds a small frame with a portrait of Rivera, indicating her love for him. The small frame was later found in Kahlo’s belongings and is exhibited at La Casa Azul today.

A private snapshot

The various rooms in the house, such as the kitchen and both Rivera and Kahlo’s bedrooms, are kept authentic for visitors to see how the house looked when the couple lived there. Kahlo’s room is still full of her personal belongings, such as her colourful clothes and costumes, for which she became famous, as well as Colombian jewelry, her diary and paintings by friends and acquaintances. Above her bed hangs a corset which she wore in order to aide her posture and support her spine, which deteriorated after a road accident she experienced at the age of 18.

At the time of her death in 1954, Kahlo was not the cultural icon she has become today; as often happens with the world’s great artists, she became famous posthumously. Kahlo’s position as part of the Mexican elite in the years after the revolution only added to her appeal and the interest in both her work and her personal life. Fuelled by her scandalous marriage to another of Mexico’s great artists, the couple represent a powerful time in Mexican art history, which affected everything from photography to local crafts and cemented folk art as part of Mexican cultural heritage.

La Casa Azul is open Tuesday to Sunday from 10am-6pm and admission is just two dollars. Coyoacán, which is a suburban area in the southwest of Mexico City was not far from W Hotel, where I was staying. The reception was kind enough to book me a taxi, but public transportation is also pretty easy and an excellent way of explore the city’s vibrant urban life. The Metrobus, a relatively new public transport bus system comprising three lines, run to Coyoacán via Line 1, while the metro line 3 stops at Coyoacán and Viveros, the latter of which is actually closer to the Frida Kahlo Museum. The taxi ride from W Hotel took only 20 minutes and cost me 15 US dollars. Coyoacán is full of cultural offerings, so the trip can be extended to visit the Trotsky Museum just a short walk away at Viena 45, and the Diego Rivera Studio Museum in neighbouring San Angel.

Mexico City and Frida Kahlo essentials:

- The official tourism authority of Mexico has its own website. http://www.visitmexico.com/

- You can visit La Casa Azul online before you get there. http://www.museofridakahlo.org.mx/EluniversointimoINGLES.html

- For a comprehensive guide to the Mexico City Metro. http://mexicometro.org/

- Frida Kahlo’s official website offers information about her work as well as a detailed timeline of major events in her dramatic life. http://www.fridakahlo.com/

- Some of Kahlo’s original paintings are exhibited at The Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. http://www.bellasartes.gob.mx/index.php/engli.html